Michael Dean’s immersive sculptural installations begin with his own writing, which he translates into physical form, from letter-like human-scale figures to self-published books deployed as sculptural elements within his installations. His materials are readily available, and include concrete and steel reinforcement bars.

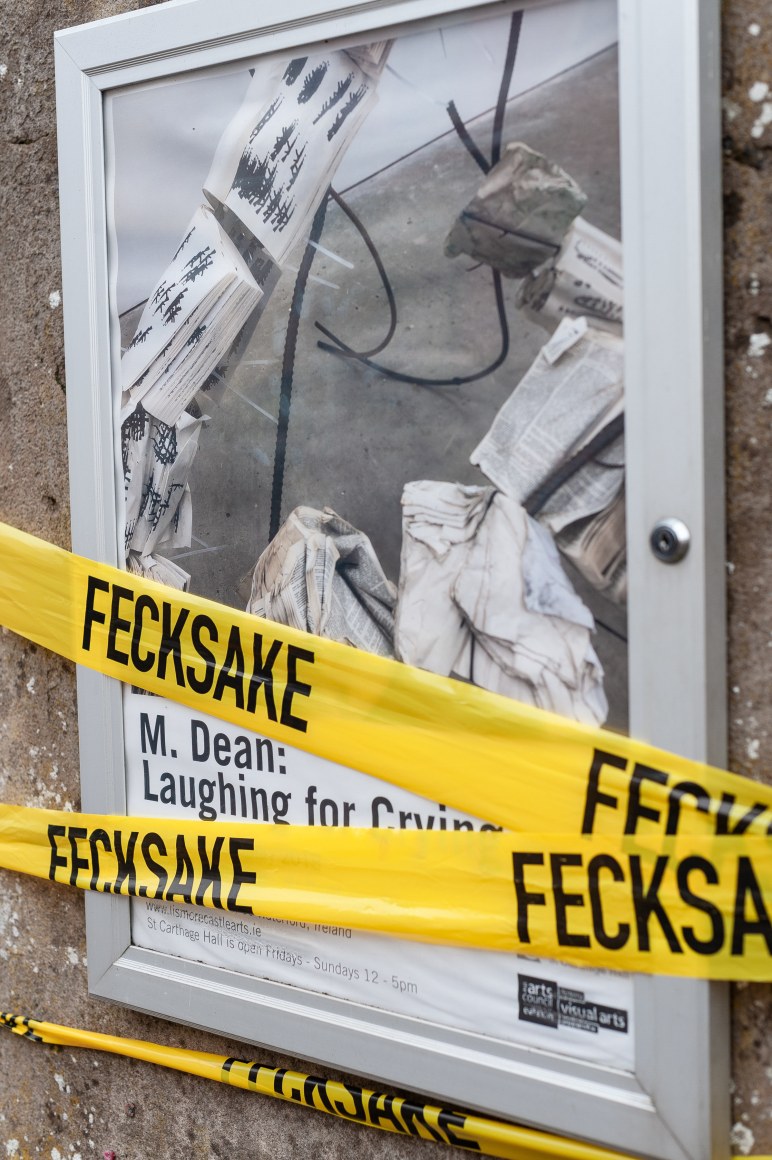

For Lismore, Michael has created a new body of work developing on from recent work which examines how our experience of text exists in the realm of the street. Commonplace signs such as hazard and police tape have been replaced by Dean’s own typographies and nonsensical poetic fragments, emptying them of their original meaning.

The transformation of written words into a language of concrete objects is characteristic of Dean’s work. Typically beginning with his own writing, he abstracts and deforms these texts into new typographies, subsequently materialised in solid, physical forms.

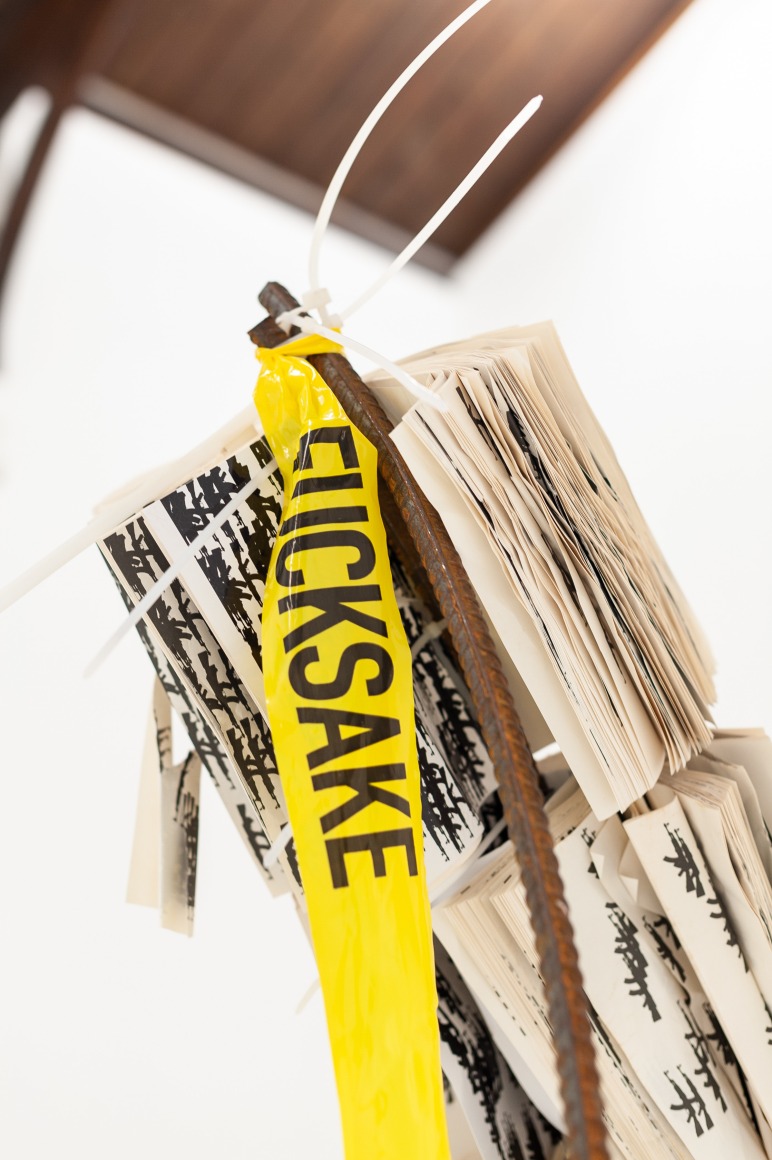

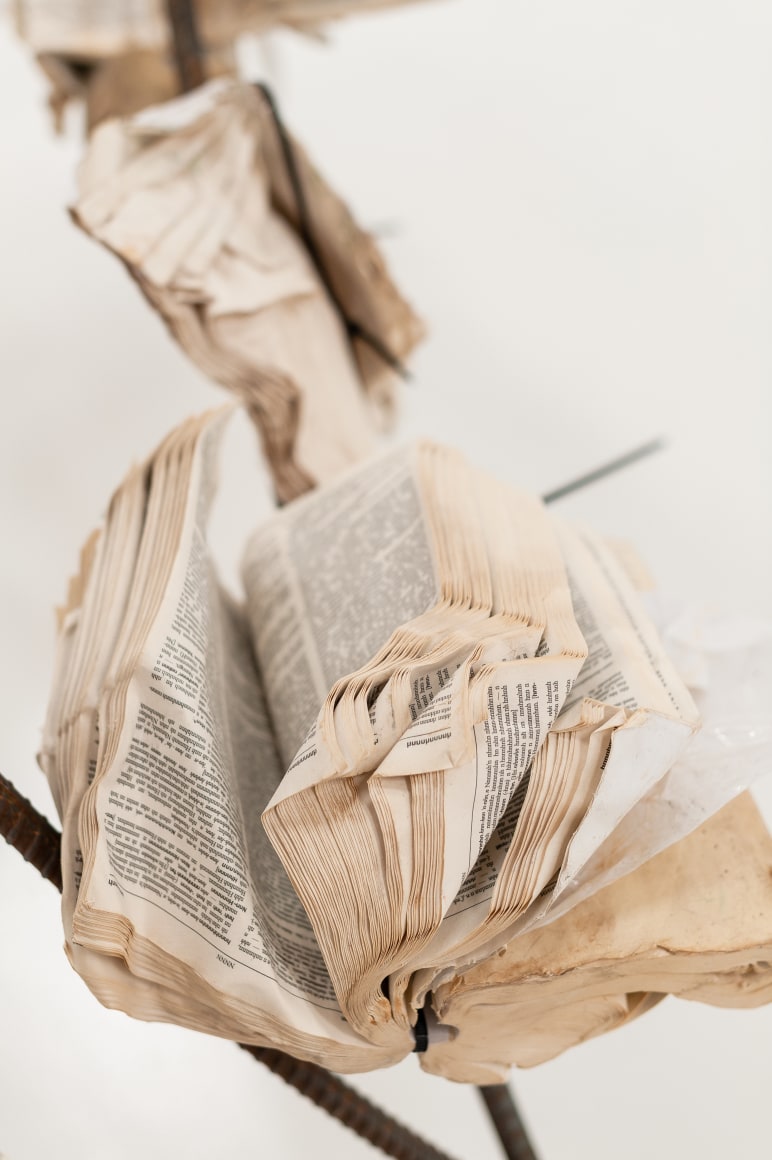

At St Carthage Hall, these writings manifest as a sculptural dove, flipped upside-down, dead on its back and carrying the weight of books strewn across its back like feathers. These books feature symbols derived from our everyday vernacular - a silhouette of an AK47 is repeated ad infinitum, spelling out ‘pollen’ in the most abstract, invisible way. Another book features a colossal dictionary of utterances, a sluggish and obsessive document of grunts and utterances, such as ‘uhhhn’ and countless variations. Ragged strands of scene tape illuminate the sculpture, with ‘fucksake’ printed on its spine, an expression of exasperation.

A stack of books on the floor, lying at the beak of the dove, ‘Love Dancing on Hate’s Grave’, printed with a heritage olive green cover and font on each page, hinting at its historic surroundings, is a stream of consciousness spanning 96 pages, permutations of violence harvested from the artist’s personal experience and the daily news, violence as irrefutable quality of articulating and conjuring being or lack of being on dying. The words are a fight between love’s ability to overcome hate. Here words are tested to their limit. We are made to think about the use and abuse of language, now more sensitised than ever, and our readiness to stand up to the relentlessness of negativity we finding ourselves surrounded by in society. An honesty hat sits beside the stack of books, and we are invited to take away a publication for a modest contribution.

The lone work in St Carthage Hall is elegantly poised, the free flowing forms delicately touching the ground and reaching outwards to the edges of the space. The walls, floor and windows have been painted white, as in a white page, emphasising the already puritanical gallery space. But the work’s delicate forms are made from rebar, a heavy, industrial, inflexible material, and betrays its own lightness. This is a harsh material, and requires a physical effort to bend into sculptural form, and underlines the tension suggested by the texts - hate versus love, soft versus hard, delicacy versus force. These contorted and often diametrically opposed forms and words hint at the dilemma of modern existence. The desire to love in the face of hate, the desire to fight back (but not fight), the desire to make and create, versus the overload of every stimulus. “What’s important for me is that my presence, my being in the world, can facilitate somebody else’s presence on a symmetrical level in relation to a possible poetic.” Contrary to suggesting that all is lost, that the negative is too much to face, Dean’s work suggests the importance of the struggle and the need to allow response and expression.